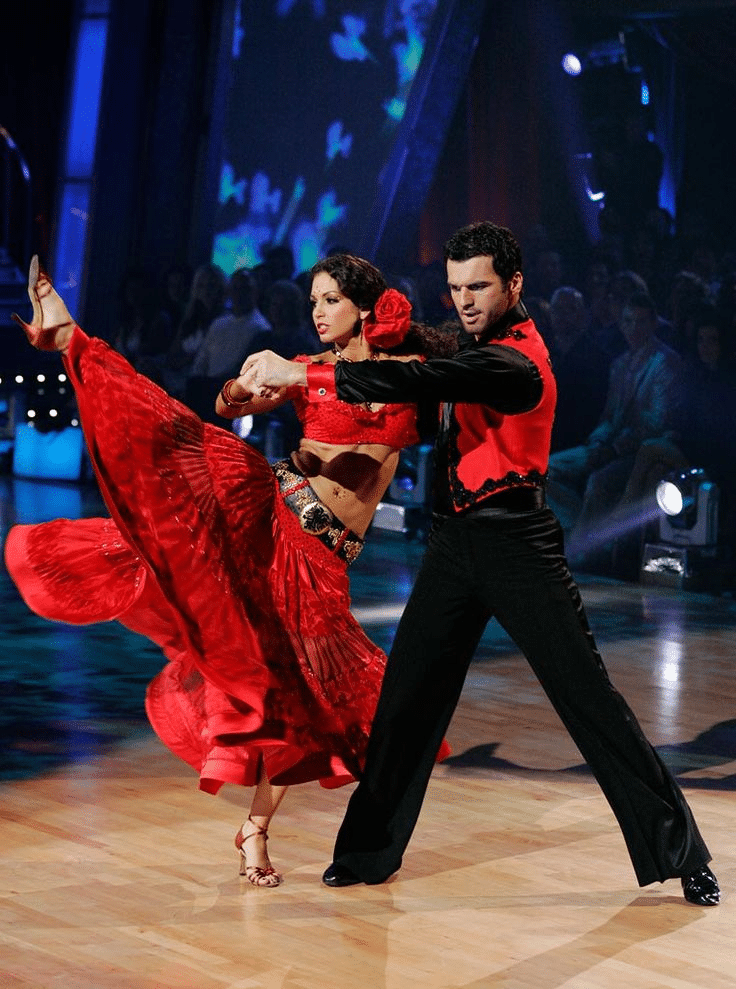

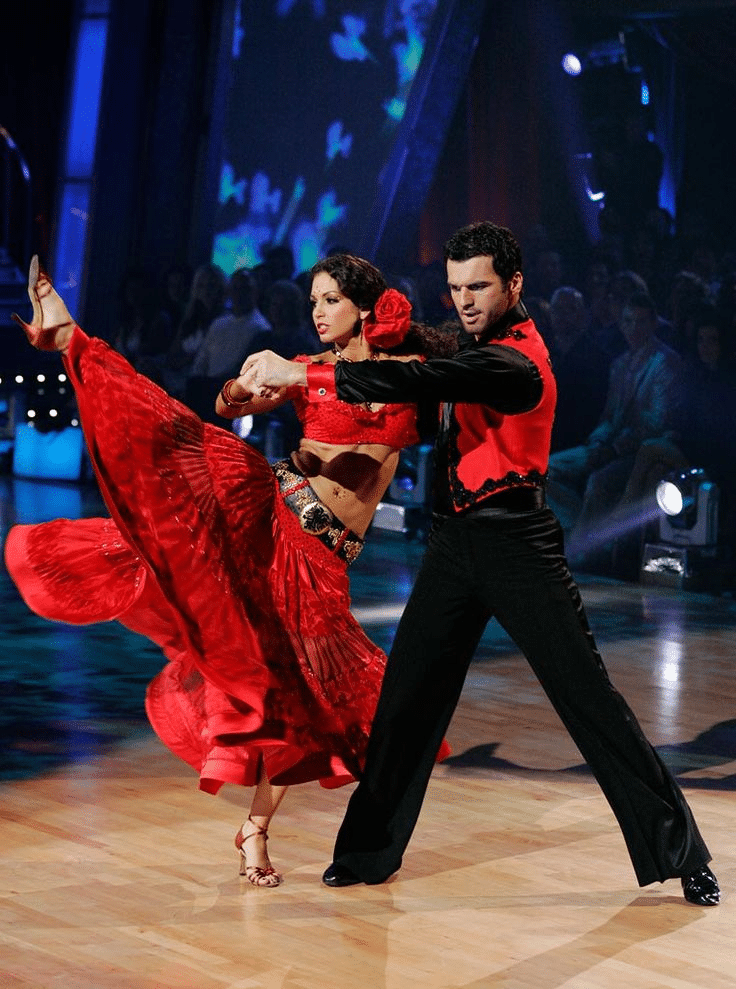

As a dancer, I have always understood how much I depend on my body. But I hadn’t ever thought about how much my world would change if it functioned differently. I thought I was rather invincible, with my young age, agility and health.

Then, one day, I couldn’t breathe. Not easily, at least. I became alienated from my body as it failed to do what I wanted and needed it to do. But let’s first back up a bit.

Before I developed long COVID, a collection of lingering negative effects from the virus, I had this subconscious expectation that I would find relief for any suffering I experienced. I have always had privileged access to the world. Being a white Jewish girl from Eugene, a small hippy town in Oregon, I have dealt with the occasional religious microaggression and familial issues, but the world has been available to me.

Last year, after my junior year at Scripps College via Zoom, I spent the summer in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, working on philosophy research and dancing in the city. I had felt bored and empty so often during the pandemic, but that summer I started to feel like myself again. I could finally dance large and uninhibitedly in a studio after over a year spent dancing in my room, banging my knees on the side of my bed. I went out with best friends who’d also migrated to New York City for the summer. Life was good.

Then, like so many others in late July 2021, I tested positive for COVID-19. Although somewhat shocked that I was a breakthrough case, I had a good feeling that my vaccine would save me from serious trouble and that after two weeks, I could return to business as usual.

During those two weeks of isolation, I slept for days. I discovered I had lost my sense of smell after my parents sent flowers. I cried a lot out of loneliness, screamed into my pillow out of anger, and stared into space, stripped and empty. My body had almost immediately weakened, shaky even when I tried to stretch.

On my first day out of quarantine, I tried to purge my body of this virus by renting out a studio to myself in the city. I spoke while I danced, shaking, rolling, sweating. When I left, I was beyond exhausted and felt a deep heaviness on my chest. Maybe that was too much too soon, I thought.

Back in Oregon, I had a week to rest before driving down to Scripps with my parents. I was ecstatic to start my senior year, in person for the first time since March 2020. On the second day of our trip, as I was carrying a lightweight table to the car, I stopped in my tracks, feeling a weight on my chest and the sudden need to sip extra air. I continued a few more steps and stopped again. Sipped more air. In the car, the weight started to feel heavier and my fear grew. I felt thirsty, but for oxygen instead of water. I started to panic, and then to cry. But the crying made it worse, so I practiced stifling my tears so as not to increase my shortness of breath.

My mom kept asking if I wanted to stop at the nearest emergency room. I had never felt so vulnerable; it was the first time I believed that something in my body could fail. We decided to pit-stop at the hospital, and learned that my oxygen levels were okay, above 90 percent, but I still felt pressure in my chest. It was safe to continue on our drive.

Finally, I was back on campus. I didn’t feel close to normal, but I told myself that if I took better care of my health, I would make a full recovery. I tried a few dance classes, but found myself gasping for air inside my mask halfway through. Each time I ignored my pain and pushed beyond my limit, the weight on my chest increased and my intense exhaustion lasted for nearly a week. I started sleeping through my 11 am ethics course and forgot to bring my computer and textbooks to class. I just couldn’t seem to get organized.

When my school doctor referred me to a long-COVID outpatient clinic, I was thrilled. To hear the phrase “long COVID” in regard to my symptoms was a relief because it meant I’d finally get help. On my first day at the clinic, I was observed during a six-minute walk, and my oxygen levels dropped so low that the lung specialist told me to absolutely stop dancing for the time being. Instead, I went to the clinic twice a week to get hooked up to the rolling oxygen tank while I walked at a slow pace on the treadmill, rode the bike at low resistance for 15 minutes and did some minimal arm exercises. I was the only person I saw below the age of 70 with an oxygen tank.

Though I’d mostly stopped dancing, I still had to choreograph a piece as part of my senior thesis that fall. In rehearsals, I tried to command the room with a motivating presence, but I often had to stop speaking to catch my breath, and I couldn’t demonstrate the choreography more than once or twice. We did our best and made something beautiful, but what I produced didn’t feel like me because I wasn’t fully there to produce it.

Not only did I have chronically low energy, difficulty breathing, dancing or walking up stairs, but this seemingly random sickness had now turned the world around me rotten. The putrid scent came on suddenly; it took me a week to realize that it wasn’t the things I was smelling, but that my sense of smell itself had changed. Many savory foods, coffee, smoke and my own body odor had started to make me gag. I would plug my nose at the dining hall. I later found out that my new condition had a name: parosmia.

Even though I was always tired, I resisted falling asleep because when I had nothing to distract me, I couldn’t ignore the heaviness on my chest or the fear, however realistic, that I might have died a premature death.

As I existed in my new state of being, I went through a long period of mourning for my past life, body, mind, smells and movement. I forgot what it felt like to sweat from moving and to be tired at night because I had lived such a fulfilling day.

I had to constantly ask for accommodations (like driving instead of walking to dinner) and to defend why I needed them. I couldn’t directly blame anyone, though. Invisible illness is difficult to remember. And I didn’t always understand what exactly someone could do to make me feel more acknowledged.

Still, there were a few friends who helped me feel less alone, who didn’t seem somewhat put off by my illness—who weren’t uncomfortable staying with it as a topic of conversation, asking questions and trying to brainstorm little solutions. They met me where Iwas, even if that meant sacrificing some of their desires.

This public health crisis has exposed the attitude our country has toward the chronically ill, the disabled, the sick, the dying and the old. Too often we hear sentiments like “It’s only the immunocompromised or elders who are dying from COVID-19. Why can’t they stay home while the rest of us live our lives?” I always knew this mindset existed, but my own health crisis allowed me to see it from a different vantage point.

The attitude is that the chronically ill, the disabled, the sick, the dying and the old are a burden to even think about. That their lives mean less. That they hold us back, instead of teaching us to see more. The truth, though, is that at some pointmost of us will be ill or experience a change in some ability or function, and all of us will die.

It was easy to see how my chronic illness made me weak. But in fact, it has given me immense strength for patience. The self-compassion required for resilience. The sureness in my own abilities, even when I knew I couldn’t yet use them.

The last year has forced me to see my own fragility but also my own humanity. We will constantly change, constantly develop new ways of moving and being. But we must keep trying to face, struggle with and see these changes. We will never escape the vulnerability of our bodies.

The post My Experience With Long COVID Forced Me to Acknowledge the Vulnerability of All Bodies appeared first on Dance Magazine.